How Humans Became Humans

A Free Book Excerpt

(My new book The Primate Myth: Why the Latest Science Is Leading Us To A New Theory of Human Nature is a story. The expression “the greatest story ever told” has already been taken by the Christ story. So consider this the second greatest story. It’s the tale of how humans became humans — and very different from apes. Here’s how it begins.)

THEOPHILUS PAINTER WAS A FUDDY-DUDDY. You can see that in a youthful snapshot, a picture taken when he was barely out of his teens. His hair is cut two-thirds of an inch above his ears, and he is wearing a tight, heavily starched three-piece suit. His left hand is firmly planted in a front trouser pocket, and his look is stern. His thin lips are sutured together, and his cobalt blue eyes project a humor less conviction.

A young Theophilus Painter.

The face displayed in the sepia-toned print is that of someone who believes that he has a special destiny. Persistently ill as a child, he was homeschooled, then sent at age fifteen to a local college. There Painter was promptly recognized as the most gifted student in his class. Four years later, in 1908, he entered Yale as a graduate student. In the photograph, his expression declares his conviction that he will be at the center of great events.

He was right about this.

Wherever he was, history was being made. He had arrived at Yale with plans to study chemistry, but he soon found himself pulled in another direction. One of his professors had made the discovery that living tissue could be grown in cell cultures, and, intent on making a name for himself, he decided to make use of the technique.

Switching over to the university’s doctoral program in biology, he turned his attention to the fertilization of egg cells. Initially, he occupied himself with spiders. Next, he examined sea urchins and lizards. Their embryonic cells are minuscule, and the work was challenging. Yet through his invention of a special knife with multiple blades, he was able to prepare slides with clearer images of the smallest parts. The process allowed him to see what had been invisible to that point: the male sex chromosomes of a mammal.

The first to reveal itself under magnification was that of an opossum. But Painter was intent on learning about humans. Obtaining sperm cells in the form he desired was not simple, and the method he decided upon would be impermissible today. An acquaintance at the Texas State Lunatic Asylum sent him the testicles of three patients who had been placed under anesthesia and castrated for “excessive” self-abuse. Painter took these and employed an elaborate process by which he could section them and arrange tissue-thin slices for microscopic inspection.

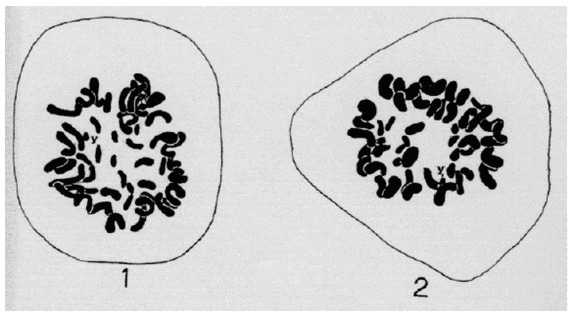

Theophilus Painter’s slides of human chromosomes.

Then he photographed the precise drawings he had made of what he had seen. What emerged from the darkroom was a series of printed sheets. On these were squiggly black lines on a blank white field. His attention gravitated toward a single pair in which one of the two lines was noticeably shorter than the other. Painter proceeded to make the bold suggestion that the abbreviated strip represented the chromosome coding for maleness: the Y chromosome.

It was an extraordinary intuitive leap. Later scholars concluded that Painter might not have identified the right coupling. Yet his deduction that the Y chromosome was a dwarf version of the X chromosome to which it was attached was correct, and it brought him instant fame.

He had made a significant error though. While the resolution of his pictures was improved by his self-created knife, his photographs were still blurry, and he couldn’t easily count up the number of chromosomes. Were there twenty-three pairs or twenty-four? Painter wasn’t certain. He had also studied the sperm cells of rhesus monkeys, and he had shown that they had twenty-four pairs. Other scientists were reporting that chimps and gorillas had twenty-four pairs. Since these species are related to us it stood to reason that humans should have twenty-four too. Perhaps with this in mind, Painter finally settled on an answer, announcing to the world that humans had twenty-four pairs of chromosomes. Almost immediately this was accepted as a fact.

Over the following decades, thousands of scientists examined reproductions of Painter’s most famous slides. Because the pictures were hazy, no one was able to say with any assurance if Painter’s tally was accurate. Few bothered to do their own reckoning of what was shown in the images, and the technology for taking photographs enlarged from microscopic sections remained primitive.

Thus, it was not until 1955—three decades after Painter had first spotted them— that Joe Hin Tjio, an Indonesian-born scientist living in Sweden, was able to do a proper recount. Tjio made use of improved staining agents. The new method provided sharper images, and, perusing his slides, Tjio realized to his astonishment that there were only twenty-three pairs—forty-six chromosomes. In the weeks and months that followed, other scientists went back, eyeing the best-known image developed by Painter.

Although it had been reproduced in millions of college and high school textbooks, to their amazement they realized that it could just as easily—perhaps even more easily—be interpreted to show twenty-three pairs with forty-six chromosomes. No one had caught the mistake.

In the meantime, Painter moved on to investigating the chromosomal structure of fruit flies.

It was an ideal subject. As they have an unusually simple genetic structure and a life span of just a few weeks, they have been the means by which scientists have learned how genes function, and once again Painter was blessed not only with perfect timing but a useful and thoroughly novel technique for his research. It was based on the realization that radioactivity causes genetic mutations.

Inducing these, he and a partner swiftly saw how genetic changes appeared and were passed on. That led to a series of scientific papers, written between 1929 and 1939, that revolutionized the understanding of the movement of genes between chromosome pairs.

Painter’s academic celebrity brought a remarkable rise in his status. Starting out as a mere lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin, he was promoted all the way up to its president. That compelled him to confront new issues. For, throughout this period, the school was segregated. One of the many people who objected to this was a young African American named Heman Marion Sweatt.

Sweatt had an amount in common with Painter. Like him, he had been something of an intellectual prodigy, and he had acquired a broad knowledge of biology. Trained at the University of Michigan, where he was a medical student, Sweatt had particularly excelled in bacteriology and immunology. But, after dropping out, Sweatt had returned to Texas and gone to work in the same field that his father had. He was supporting himself as a mailman.

Finding that even opportunities for promotion in the post office were denied to him, Sweatt became a civil rights activist and a columnist for a Black newspaper. Over time, he became increasingly aware that defeating Jim Crow required legal skills. So in 1946 he met with Painter to make a request: The University of Texas’s law school should end its discriminatory admission practices, and he should become its first African American student. When Painter told him that this was impossible, Sweatt filed a class-action lawsuit naming Painter as the defendant.

Sweatt’s able lawyer, Thurgood Marshall Jr., brought the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Known today as Sweatt v. Painter, the lawsuit led directly to another case in which Marshall was the lead attorney: the Brown v. Board of Education decision that ended legal segregation.

Like many people of his era, Painter thought that Blacks and Whites must be different in their fundamental biology. So when he reported his results on chromosomes, he provided separate data on the two groups. The implication seemed to be that it was noteworthy, even unexpected, that Blacks and Whites had the same number. Perhaps not surprisingly then, Painter did not fight against the belief that Blacks and Whites should be kept apart. Dutifully, he obeyed the instructions given to him by the school’s Board of Regents.

These were to keep Sweatt out, and month after month, over full four years, he refused Sweatt’s admission. Painter began by offering Sweatt scholarship money to attend an out-of-state law school. Then he tried to arrange for Sweatt to go to a newly constructed Blacks-only law school in Houston. This was to be housed within three basement rooms that would include a small law library. This contrasted with the law school in Austin, which had a whole building, sixteen full-time faculty members and 65,000 volumes. Nonetheless, Painter insisted that the school in Houston would be just as good. These two beliefs—Painter’s erroneous assertions about the number of human chromosomes and the notion that schools can be “separate but equal”—have a certain kinship.

Both are examples of a phenomenon that is more commonplace than we might care to admit. Dubious opinions are offered up, and they live on for decades or even centuries. Often these false claims are easy to disprove. All that is required is dispassionate study. There are countless illustrations of this, cases in which absurd notions were accepted for long periods during which overwhelming proof of their error was ignored or rejected. Sometimes those who are the most mistaken are research scientists, men and women trained in the objective analysis of evidence.

Why is it that people become so committed to false beliefs? That riddle brings us to a larger enigma that Painter was investigating as he was peering into his microscope. What is a man? Attached to that is a second puzzle: How did we become human?

(To keep reading this opening chapter, go to https://www.amazon.com/Primate-Myth-Latest-Science-Theory/dp/B0F27ZZ9ZN to purchase a copy.

You have me hooked! I’m buying the book!

I got your book and it is fascinating!