How Humans Became Humans, Part Two

A Second Free Excerpt From My New Book On Human Evolution

(In April, a massive study by the world’s top geneticists was released. It proved that humans are not closely related to chimps. It turns out that we have diverged widely from our ape ancestors, and we are ten times more distinct genetically from them than was previously claimed. One reason why we were set out on a different path is that we have a completely different diet than nearly all primates. That meant that we had to evolve to be a very different animal. At the same time, although we have had a meat-based diet, we are not anatomically similar to carnivores. One chapter in my new book The Primate Myth: Why the Latest Science Leads Us To A New Theory of Human Nature examines this puzzle.)

CARNIVORES LOVE SLEEP.

THAT’S ESPECIALLY true when they are apex predators. Male lions are typical. They are dead to the world for up to 20 hours each day. Primates also tend to be fond of slumber. At the upper limit is the three-striped night monkey. Found in the Amazonian rainforest, he drowses for an average of 17 hours each day. Two species of macaques, gray mouse lemurs, ring-tailed lemurs, and cotton-top tamarins catch more than 15 hours of shut eye. At the low end of the spectrum are chimpanzees. They take in between 9.67 and 11.5 hours.

So, as humans are meat-eaters and we are supposed to be primates, you might assume that we would be superior sleepers. But here’s the curious thing: No primate whose nocturnal resting patterns have been studied spends less time at it than we do. While the range among primate species varies greatly, it is always far in excess of that observed among humans. As adults we typically get less than seven hours per night of sleep.

We also defy another rule of great apes in our resting patterns. Chimps, gorillas, and orangutans build nests. We do not. What explains this? A clue might be found in looking at what sort of mammals tend to function on little sleep. The answer is large-brained herd animals, such as giraffes, horses, and elephants. If they sometimes look a bit ragged at the edges, there is reason. Since these creatures must stay alert to avoid becoming prey, all of them sleep less than five hours each night. Were we to plot ourselves on a graph, we would fall somewhere between the primates and the ungulates.

This makes sense when we begin to think about how we live. Lions and tigers have the bodily tools to easily kill any creature that might threaten them, and most primates can climb trees to escape predators. For most of our evolutionary history we have been more like giraffes and elephants.

Our evolution has arisen with an ever-present fear as our physiology and anatomy are different. We had to be awake and alert. Our collaborative instincts have been employed not only in hunting but in jointly protecting ourselves from attacks. Wandering off alone meant likely death. That fact has compelled us to develop a certain delicacy in our manners and a high degree of social engagement. Although we have evolved to hunt and to consume meat, we are not obligate carnivores. This is a term for an animal that depends exclusively upon flesh as a source of its nutrients.

These creatures are within a category referred to as hypercarnivores. It is a select designation. Among mammals it is reserved for a small number, including big cats, some wild dogs, seals, sea lions, polar bears, and dolphins. Zoologists distinguish these animals from mesocarnivores or facultative carnivores. Most animals within the carnivore order are of this latter type. They have a diet that is mostly made up of meat, but on occasion they will also eat insects, mushrooms, fruit, and grasses. This is how skunks, foxes, raccoons, and mongooses feed themselves.

It’s worth noting that the hypercarnivores that hunt in packs are among the tamest animals. When we place dolphins and sea lions in zoos, we are setting them in environments whose territory is just a tiny fraction of what they have been accustomed to out in the ocean. Yet they will follow our directions, learning tricks and performing for us in return for treats. Similarly, dogs have proven to be the most easily domesticated and most affectionate of all pets.

Mesocarnivores, however, tend to be less docile.

Until now I have not said how much meat Homo sapiens have typically eaten during our lengthy process of evolution. It is not unusual for present-day hunter-gatherers to take 30 percent of their calories from meat. Long ago though it was much more. In some cases, it was 80 percent of the total.

According to a study of 229 hunter-gatherer societies, just 14 percent of prehistoric tribes derived less than half of their calories from animal sources. On average our ancestors were taking in twenty times as much flesh as chimps and infinitely more than gorillas and all other primates. The 55 to 65 percent level that is thought to have once been average for humans is several times as much as black bears consume. It may be five to six times as much. This amount of meat consumption places humans alongside lynx, bobcats, and otters as mesocarnivores.

That we became hunters before we learned the arts of livestock raising is one of the most extraordinary facts in the history of evolution. Creationists like to question evolution by pointing to the eye. Because its function involves the coordination of so many different parts, sight is remarkable. But one might argue the fact that humans learned to hunt is more startling.

To get a further sense of this, let’s look at the mammal order as a whole. One difference between warm- and cold-blooded creatures is that while most fish and reptiles are carnivores, the vast majority of mammals consume plants. This is a consequence of the high rate of mammalian energy consumption. Maintaining our high body temperature requires enormous amounts of fuel. Mammals constantly burn huge quantities of it, and, since this energy ultimately comes from plants, there must always be several times as many mammals eating plants as there are carnivorous mammals consuming those herbivores.

Were this not the case, meat-eaters would quickly run out of prey and die out as the original source of energy for animals is the plants that use chlorophyll to turn the sun’s energy into edible sources of power: sugars, fats, and proteins. To put this in concrete terms, think of a big cat. Male lions eat between ten and twenty pounds of meat each day. That requires a lot of prey. During the course of a year, a single male lion consumes between fifteen and thirty-five animals the size of an adult antelope.

Since there are certain inefficiencies in digestion and a loss of energy in the transfer of energy from plants to the animals that digest them, a great many gazelles and antelopes have to chew up a huge swath of grass for that one lion to feed himself.

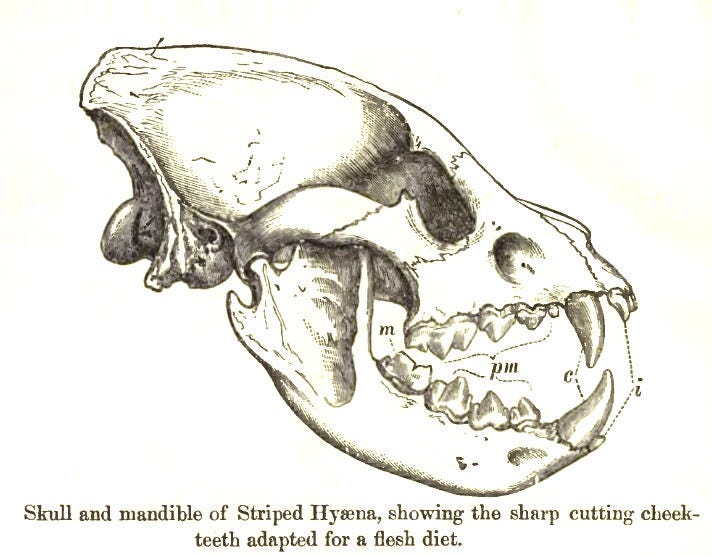

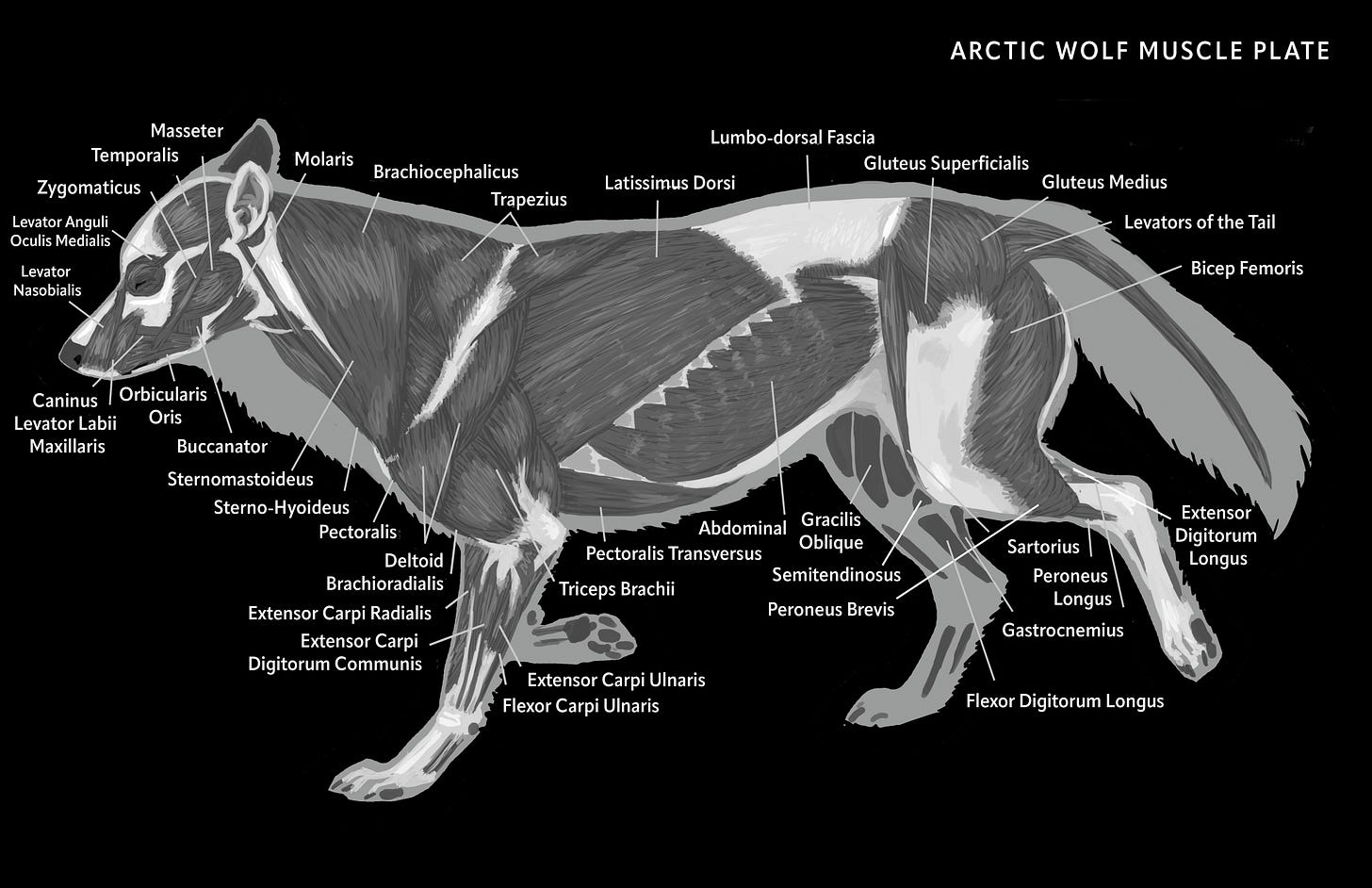

Consequently, of the more than 5,400 mammals, just 279 fall into the order of carnivore, and many of those are actually mesocarnivores or omnivores. Further, within the order, there are just nine families that live on land. These are the canids (dogs and wolves), felids (cats), ursids (bears), procyonids (raccoons), mustelids (weasels, badgers, otters), mephitids (skunks and stink badgers), herpestids (mongooses), viverrids (civets and genets), and hyaenids (hyenas). What they have in common are big teeth with glaring canines, powerful jaws and chest muscles, sharp claws, four legs, and a highly developed sense of smell. Each has a purpose and a function, and it may be worth reviewing them since, as we have mentioned, we don’t have any of those.

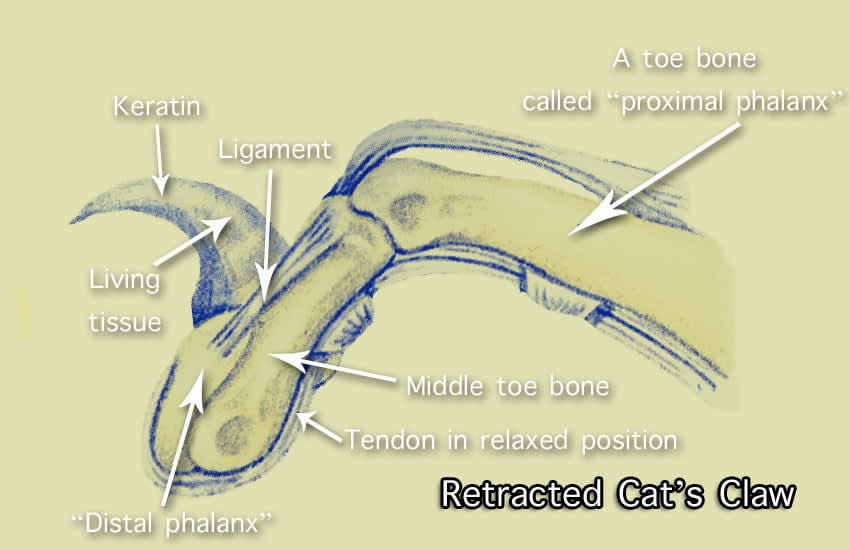

The teeth and the canines, along with the mighty jaw, are for tearing flesh apart and for striking at key veins and arteries, like the carotid and the jugular. The outsized chest muscles assist with pouncing on and pinning down the prey. The claws are not like our nails. They are not cuticles. They pass through the paws, connecting to bone and attaching to tendons. They aid in ripping up and grasping a victim, and they can be employed in climbing. The quadruped form is ideal for speed, balance, and agility, and the carnivore’s enhanced olfactory organs provide it with an innumerable number of clues that can be used in tracking and hunting.

The tendons pull on the distal phalanx holding the claw, which moves the claw out. The tendons are operated by muscles in the cat’s leg.

Hyena skull and teeth.

Wolf musculature.

Weasel nose.

Cheetah legs.

Without these, we’re like Muggsy Bogues. For those not familiar, Bogues is a former professional basketball player. He played in the NBA for ten seasons, and he ranks in the top twenty-five players all-time in assists. Yet he stands five-feet-three-inches tall. He made up for that with a number of astonishing skills. He had amazing quickness and strength. Those matched to extraordinary peripheral vision, anticipation, and hand-to-eye coordination. And he played with uncommon passion and energy. For all that, he’s still a very rare exception to the rule that short men can’t excel at basketball.

That humans learned to hunt is equally remarkable as we have none of the obvious requirements for the task. Evolutionary biologists often point to our use of tools as a substitute, but advanced tools appeared tens of thousands of years after the first humans were born. A hundred thousand years ago Homo sapiens could do no more than attach sharpened pieces of bone or slivers of rocks of two or three inches in length onto wooden poles.

Consider that even with a hand gun it’s exceedingly dangerous, acting alone, to try and approach a stampeding herd. Yet we know from archeology that by the end of the last ice age humans were hunting mastodons and woolly mammoths. Nineteenth-century big-game hunters found that it could take up to thirty-five shots with a regular gun to bring down an elephant. For this reason, they came to use giant-bore weapons known as elephant guns. Most notorious was the .577 Black Powder Express. These rifles carried a three-inch long cartridge weighing more than four ounces. In the present day, poachers will first poison elephants with cyanide and then fire at them with automatic rifles.

So how was it possible for us to avoid getting killed hunting woolly mammoths when our weapons were spears, bow and arrow, and, at best, pikes? Present-day African elephants are enormous creatures. The males can weigh 13,000 pounds. But wooly mammoths were even bigger. Some weighed up to 20,000 pounds, and their tusks were up to fifteen-feet long.

To slay them we had to evolve so that with great patience we could engage in extremely close collaboration. Remarkably, we then learned how to kill the mastodons and wooly mammoths so efficiently that we drove them to extinction.

The meaning is clear: To survive as hunters, we needed to undergo a profound change in our nature, and development of speech was almost certainly part of that. Bear in mind, too, that even with the natural tools of the carnivore—the big teeth, the sharp claws, the speed, the keen sense of smell, and the powerful chest muscles for pouncing on a targeted creature—few predators attack animals that are as large as they are.

If you have a housecat, you may know this already as while housecats are masterful at killing mice, they won’t pursue rats. The predators that slay animals bigger than they are fall into two categories. Either they are exceedingly patient hunters like ermine and Komodo dragons, or they are stealthy pack animals that work together closely and hunt as a group. That’s an apt description for hyenas, wolves, killer whales, and dholes (a species of African dog).

Because humans were pursuing animals that were one hundred times our size and doing so without the natural carnivore equipment, we had to combine those traits and then make use of speech in addition. We had to evolve so we were capable of being even more cooperative than wolves and hyenas, and more patient than Komodo dragons. Simply put, we had to stop thinking and acting as primates generally do.

How, you might ask then, does this help us unlock the mysteries of human nature?

To find out more, go to https://www.amazon.com/Primate-Myth-Latest-Science-Theory/dp/B0F27ZZ9ZN to purchase a copy.

I got my copy of the book and your chart on page 1 is terrific! Really educational. I don't know if you cover this, but concurrent with the massive increase in human brain size was a radical change in the size and function of the large intestine. The large intestines of chimps/apes (very long) are able to convert plant matter into protein. Humans lost that ability during the millennia of evolution away from apes, and our (very short) large intestines are mainly for water resorption. During those millennia we were almost exclusively meat eaters, and we mastered fire and cooking. Our teeth do not need to be able to rip flesh, as it can be cooked. And, picture a human from hundreds of thousands of years ago trying to eat a plant. There are millions of plants to choose from, and 99.9% of them would make them sick or be non-nutritious. It was only 10,000 years ago, with the advent of agriculture, that we figured out which plants we could eat and digest. And, that high carbohydrate diet, inconsistent with our evolution, is the cause of cardiovascular disease. OK, good talk!

This is so fascinating. I am loving your book. I got it on Kindle and in paperback so I can lend the latter to family and friends.